Welcome!

This blog provides an opportunity for the WHOI community to get to know our students a little better, a forum to share information with the students, and a window into the JPBO for the outside world. The primary focus is on the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Biological Oceanography. Please send suggestions for blog content to atarrant (at) whoi (dot) edu.

On November 17, Taylor Sehein successfully defended her thesis, entitled “Trojan Horses in the Marine Realm: Characterizing Protistan Parasite  Ecology in Coastal Waters.” Taylor combined high-resolution sampling with microscopy, molecular approaches and modeling to study the ecology of Syndinian parasites within protist communities. Her defense followed a hybrid model in which some committee members attended in person, and the remainder of the audience attended virtually.

Ecology in Coastal Waters.” Taylor combined high-resolution sampling with microscopy, molecular approaches and modeling to study the ecology of Syndinian parasites within protist communities. Her defense followed a hybrid model in which some committee members attended in person, and the remainder of the audience attended virtually.

Taylor was advised by Dr. Ginny Edgcomb. After graduation, Taylor will begin a postdoctoral position with Dr. Laura Katz at Smith College, where she will study protist evolution. We congratulate Taylor and wish her all the best in her future pursuits!

Nadège Aoki and Kharis Schrage were both awarded Ruth D. Turner Scholarships for 2021.

Nadège’s proposal was titled “Documenting the effect of exposure to impulsive pile-driving noise on behavior of a temperate coral species, Astrangia poculata”. She’ll be exposing local corals to noise recorded from an offshore wind farm construction project and measuring their behavioral response (specifically the retraction/extension of their polyps from their protective skeletons).

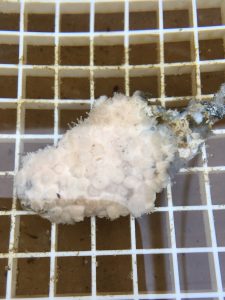

Nadege setting up an experiment with corals |  Northern cup coral (Astrangia poculata) |

Kharis’ proposal was titled “Coupling of Life History Strategies of Benthic Invertebrates During the Polar Night.” The award will fund a field trip to the Arctic in January to study the seasonality and spatial distribution of larval and adult benthic invertebrates in an Arctic fjord.

ice from the bow of the Polarstern during a summer trip to the Arctic

Kharis seeks to identify not just species composition in larvae and adults but to couple these data for a more comprehensive understanding of the bottlenecks affecting invertebrate settlement success and survival. She is specifically choosing to focus on species reproducing in the polar night as there is next to nothing known about reproduction during this time period.

Seven students have entered the JPBO in Summer and Fall 2020. Most of them were able to “get their feet wet” in their new labs this summer, and they are now all digging into their first semester of classes. We look forward to meeting these students in person over the coming year, but in the meantime, here are a few ‘fun facts’ about them.

Not pictured/in progress: Kela Bakari and Michael Meneses

Jaida Elcock is a member of Camrin Braun’s lab and comes to us from the University of Washington. Shei s interested in elasmobranch movement ecology and habitat use. She writes, “I am in love with the ocean despite growing up in the desert and I enjoy communicating science through social media.” Jaida also co-founded a nonprofit organization in June of 2020 called Minorities in Shark Sciences (MISS) that is geared towards supporting women of color in the field of shark science. Jaida has many talents: she was a springboard diver for 7 years and also plays the flute.

Jaida Elcock is a member of Camrin Braun’s lab and comes to us from the University of Washington. Shei s interested in elasmobranch movement ecology and habitat use. She writes, “I am in love with the ocean despite growing up in the desert and I enjoy communicating science through social media.” Jaida also co-founded a nonprofit organization in June of 2020 called Minorities in Shark Sciences (MISS) that is geared towards supporting women of color in the field of shark science. Jaida has many talents: she was a springboard diver for 7 years and also plays the flute.

Emmett Culhane Emmett is interested in the way that the movement of water structures the biology and ecology of the open ocean. As a member of Dr. Camrin Braun’s lab, his primary research focus is on the interaction between large predators and the dense communities of fishes in the Ocean Twilight Zone. Prior to joining the WHOI community, Emmett worked as a performer on multiple DARPA programs under the Information Innovation Office (I2O), where he contributed to research efforts in computer science for counter intelligence purposes. In the spring of 2020, Emmett completed a MSc in computer science at Yale University. Emmett lives with his partner and their giant hound dog Lizard King, and is an inexorable fisherman.

Katherine (Kate) Lane researches marine microbes using molecular, genetic, and computational tools in Maria Pachiadaki’s Lab. Previously, she received a Masters in Population Biology from UC Davis in Prof. Jonathan Eisen’s Lab, worked as metagenomic computational staff in Prof. Jill Banfield’s Lab at UC Berkeley, and completed her BA in Biology at Macalester College. Outside of the lab, Kate likes backpacking, gardening, and classical music.

Junkun Ren graduated from Shanghai Jiao Tong University with a B.S. in food science and engineering, and from Harvard School of Public Health with a MS in epidemiology. Shee also worked as a research assistant in epidemiology at Dartmouth College and in theoretical ecology at Peking University. She works with Prof. Mick Follows and is interested in marine ecology-related questions in general. In her spare time, Junkun enjoys reading fictions and playing video games. Junkun also tells us that she really loves cats and hopes she can have one in the near future.

Serena Sung-Clarke graduated from Swarthmore College in 2019 with a B.A. in Biology and Political Science. As an undergraduate, she conducted research on the immune system pathways of a symbiotic marine cnidarian. Before starting the Joint Program, she worked at a consulting firm on projects for U.S. EPA related to watershed protection, chemical contamination, and drinking water infrastructure. Serena has joined Mike Brosnahan’s lab and is looking forward to studying the biology and dynamics of toxic harmful algal blooms. In her free time, she enjoys reading, riding her bike, and trying out the ice cream shops of Cape Cod (very open to recommendations/opinions).

Serena Sung-Clarke graduated from Swarthmore College in 2019 with a B.A. in Biology and Political Science. As an undergraduate, she conducted research on the immune system pathways of a symbiotic marine cnidarian. Before starting the Joint Program, she worked at a consulting firm on projects for U.S. EPA related to watershed protection, chemical contamination, and drinking water infrastructure. Serena has joined Mike Brosnahan’s lab and is looking forward to studying the biology and dynamics of toxic harmful algal blooms. In her free time, she enjoys reading, riding her bike, and trying out the ice cream shops of Cape Cod (very open to recommendations/opinions).

The George “Gera” Pavlovich Panteleyev Award is conferred annually on the MIT-WHOI or WHOI Graduate Student in the graduating class for that academic year who best exemplifies the commitment to improving the graduate education experience and graduate student life at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Christina “Chrissy” Hernández was named the award recipient at the 2021 Joint Program graduation ceremony.

Christina received her doctoral degree in Biological Oceanography in February 2021 under the supervision of Dr. Joel Llopiz. Her thesis title is: Distribution, Growth, and Transport of Larval Fishes and Implications for Population Dynamics

Some excerpts from nominations:

- Nearly all nominators commented on the recipient’s significant contributions towards making WHOI a more inclusive environment. For example, Chrissy organized a widely attended CommnuiTea, served on the WHOI Workplace Climate Committee for several years and, as most succinctly stated by nominators “I can’t think of a DE&I committee or movement that Chrissy wasn’t involved in”, and “Chrissy’s activism and advocacy has left a huge mark on the Joint Program”.

- Many noted that Chrissy’s community service and leadership extended well beyond WHOI and the JP. For example, Chrissy was a student rep for the Oceanography Society and was a founding member and President of the Society for Women in Marine Science, now a non-profit with many chapters. Within the JP and beyond, Chrissy always used their voice to raise awareness and lift up others.

This spring JPBO student David Gellar-McGrath was awarded a fellowship from the Department of Energy’s Office of Science Graduate Student Research program (DOE SCGSR). David is co-advised by Dr. Virginia Edgcomb (WHOI Marine Geology and Geophysics Department) and Dr. Maria Pachiadaki (WHOI Biology Department). David’s research broadly focuses on developing tools to analyze metabolic pathways in metagenomic and multi-omics datasets, and applying these tools to characterize the metabolic potential within oxygen-depleted benthic environments.

The SCGSR research program “provides supplemental awards to outstanding U.S. graduate students (US citizens or lawful permanent residents) to pursue part of their graduate thesis research at a DOE laboratory/facility in areas that address scientific challenges central to the Office of Science mission.”

David’s fellowship was awarded in the priority area of Computational Biology and Bioinformatics. It will allow him to work with researchers at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) on on improved metabolic modeling and prediction methods for multi-omics datasets.

The MIT-WHOI Joint Program PhD students have launched a newsletter called Through the Porthole. They state, “our goal is to make information about graduate school in the geosciences, and the JP in particular, more accessible to undergraduates with diverse educational backgrounds. We provide practical advice about how you can make grad school in the geosciences happen.”

To date two issues have been published, and in the second JPBO student Lei Ma is featured in the “Student Spotlight.”

In the article, Lei provides valuable advice to undergraduates considering careers in ocean sciences. She highlights her own training as a microbiologists and emphasized that students don’t necessarily need to come to graduate school with previous experience in oceanography or marine science. She encouraged undergraduates to take advantage of opportunities to gain formal training in data analysis and statistical analysis. From the article I also learned that Lei is proficient in Tae Kwon Do.

I applaud the JP students on this effort, and I encourage everyone to check out this newsletter. Please share the link with undergraduate students and faculty at undergraduate-serving institutions.

The Atlantic just published a great story about Lauren Dykman’s work on deep-sea parasites

Even if you didn’t know you were interested in deep-sea parasites, I recommend the article. It’s written in a really compelling way!

Over the past few weeks, we have had two big reasons to celebrate: Christina (Chrissy) Hernández and Kevin Archibald successfully defended their Ph.D. theses on October 15 and November 13, respectively. Both Kevin and Chrissy have been valued members of our WHOI community and we wish them the very best in all their future pursuits.

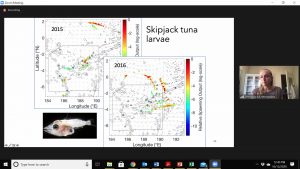

Chrissy’s thesis is entitled “Distribution, Growth, and Transport of Larval Fishes and Implications for Population Dynamics.” She will be starting a postdoc at Cornell University, working with Steve Ellner (Cornell), Robin Snyder (Case Western Reserve), Peter Adler (Utah State) and Giles Hooker (Cornell). The project investigates life history evolution by employing databases of population data (COMADRE, COMPADRE, and PADRINO databases) to explore relationships between species traits and population outcomes.

Left: Chrissy after her successful defense with a whimsical cake made by JP student Jen Karolewski. Four white chocolate “otoliths” were hidden throughout. A person of many talents, Chrissy even knit the top she is wearing in the photo!

Above: Screen shot from Chrissy’s defense. If you look closely, you might notice a larval tuna that has already eaten another fish…it can be a rough world out there!

Kevin’s thesis is entitled: “The Role of Zooplankton in Regulating Carbon Export and Phytoplankton Community Structure: Integrating Models and Observations.” He will be starting at postdoc at UC Santa Barbara working with Holly Moeller (a JP alum and former WHOI postdoc). During his postdoc, Kevin will be modeling the role of mixotrophic plankton in pelagic ecosystems and investigating potential climate feedbacks associated with changes in rates of mixotrophy within these communities.

Kevin cutting the cake after his virtual defense. “Word on the street” is that his co-advisor Mike Neubert dropped off a bottle of champagne the day before as a contribution to a socially distanced celebration.

(This post was written by JPBO student Lauren Dykman, October 2, 2020)

The order came suddenly: work from home. We had only a handful of days to move out of our labs at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and into home offices. We all started to think creatively. Personally, I had planned to spend the next several months dissecting frozen animals from deep-sea hydrothermal vents, which I’d managed to offload from the research vessel Atlantis only hours before WHOI closed. I couldn’t work with these samples at home, so I had to come up with a new research plan. So, how does a marine ecologist work from home? This is the story of how I ended up with hundreds of snails and their parasites in my bedroom closet.

For the last two summers, I had been studying parasitic worms called trematodes that live in Atlantic mud snails, which are abundant in estuaries around Cape Cod. Last summer, an undergraduate lab mate and I discovered that the composition of parasites in snails is very different across estuaries, and changes over time. I was curious what factors lead to these patterns in parasite abundance and diversity, so I planned some experiments.

First, I needed a lab. Back at WHOI, I had access to a room with aquaria and flowing seawater, plus a dissecting station with a nice microscope. So, I got permission to enter the Institution for one day to grab a carload of supplies and move them down to my home basement. After an afternoon of sweeping, rearranging, and setting up crude lighting, “basement lab” was born.

I planned a number of surveys and experiments to better understand the biology of the snails and their parasites. These required one of an ecologist’s favorite sets of tools: a transect tape and a quadrat. The transect tape is a large tape measure that lets a researcher lay out a line in order to sample the same place over time. The quadrat is a square frame divided into smaller squares that allows a researcher to count animals or plants (or whatever) in a known area. Both these tools reduce bias and inconsistency in surveys. The problem was, I didn’t have a quadrat. I solved this with a trip to the hardware store and an afternoon of arts and crafts. PVC pipe, along with zip ties and duct tape, is one of the essential building materials of a field ecologist.

Building a quadrat with supplies from the hardware store.

Going into the field during a pandemic was strange, needless to say. In prior summers, trips to beaches and estuaries were a fun reprieve. Now, they involved nervously dodging summer traffic in full parking lots, wearing a mask. I felt self-conscious being that mysterious person laden with gear who, rather than joining the sunbathers on the white sandy beaches, veered inland into the marsh to wallow in mud.

Avoiding crowds in a Summer 2020 beach parking lot on Cape Cod (left). Knee-deep in mud (right).

A 5am survey at Waquoit Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve was exhausting yet beautiful (left). Using the quadrat and transect tape at Little Sippewissett Marsh (right).

The first part of the study was figuring out what percentage of snails were infected with parasites. The parasites in question, trematodes, are worms that live in the snail’s gonad (yep) and churn out clones, which leave the snail as swimming larvae to seek their next host. To check for parasites, I collected snails, placed them in individual wells of sea water (which I called “snail condos”), and inspected the water for swimming parasite larvae after two days . This method of screening for infection was noninvasive, meaning I could return the snails to their natural habitat after their brief “vacation.”

Placing snails into “condos” at the patio table (with home lab-appropriate footwear).

Video of swimming parasite larvae after they have left the snail host. These are called cercariae, and they are less than 1 mm in length.

The first time I tried this procedure at home I ran into a problem. From reading scientific papers, I knew trematode parasites release larvae most reliably at warmer temperatures. But “basement lab” was very cold. I was afraid the cold would skew my results, and I wouldn’t find any parasites, even if the snails were infected. Gradually, and somewhat reluctantly, I accepted the obvious solution. This is when I moved the condos, the snails, and their associated parasites into my bedroom closet. During this period of quarantine, our house occupancy swung between 2 and 202. At night, I was haunted by the sounds of snail shells clicking against the plastic boxes. There is an ironic humor in this situation that would make a parasitologist chuckle: some parasites are able to manipulate their host’s behavior to make further infection more likely. Here, in an extreme case of host manipulation, these parasites had enticed me to invite them into my home by tempting me with a chance at completing a PhD.

The day I invited marsh snails into my closet.

The results of the “closet parasite surveys” were stark: the percentage of infected snails varied drastically, even over short distances within a single estuary. I started to wonder, could the movement of snails, rather than just the processes of parasite infection and recovery, contribute to these patterns? Perhaps snails hardly moved, but the chance of getting infected varied across the estuary. Or alternately, infected snails may be more likely to migrate to certain locations than uninfected snails. This led to the most fun experiment of the summer – figuring out how snails move.

Another classic technique in field biology is the “mark-recapture study.” This involves marking animals, releasing them, then finding them at a later time. I spray-painted several hundred snails in our driveway, released them at a single point in the marsh, returned five days later with a tape measure, and squelched knee-deep in mud to each painted snail, measuring its progress.

During this process, I set up a GoPro on time lapse, curious what it would reveal about the secret lives of snails. This turned out to be the most revealing method, as it proved snails can really cruise! Sometimes, snails would move in patterns that appeared random and end up evenly spaced. At other times, snails would all travel together in one direction, a behavior I called “streaming” or “herding.” In some places, snails would form huge, stationary piles, or “aggregations.” Next summer, I want to plan experiments to figure out what causes snails to switch between these different patterns of movement, and how host movement functions to disperse parasites.

Working from home required everyone to shift plans and perspective. For my research, as for my personal life, it caused me to live and think locally. I allowed myself time that I otherwise would not have taken to truly see the ecosystems right in my own neighborhood and become acquainted with the lifeways of my animal neighbors. This reawakened an appreciation and fascination for the mysteries and intricacies that play out right in front us, every day. Science does not necessarily require expensive instruments or international travel. Sometimes it just takes some PVC pipe, a bit of home improvement, and a whole lot of mud.

Time lapse video of snails "streaming" at Little Sippewissett Marsh.

Time lapse video of painted snails released next to aggregations at Little Sippewissett Marsh.

Six students have entered the JPBO in Summer and Fall 2020.With the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis, the students have identified creative ways to engage in online learning and socially distanced research. We may find 2020 to be something of a mixed bag overall, but we have nothing but enthusiasm for our newest colleagues. We look forward to welcoming these students in person, but in the meantime, here are a few ‘fun facts’ about each of them.

Kharis Schrage graduated from William and Mary in 2017 where she studied biology and marine science and did research on intertidal community ecology and marine invertebrate development. After graduating she spent the last few years as a field technician including on a remote salmon monitoring project in Alaska, a sturgeon study in Georgia, and two different zooplankton groups in Antarctica. Kharis is now in Kirstin Meyer-Kaiser's lab hoping to study the reproductive ecology and larval biology of marine benthic invertebrates in the Arctic. Outside of science she loves to travel, dive, hike, and make anything from coffee tables to homemade pasta. |  Caroline Rzucidlo graduated from Fairfield University with a B.S. in Biology where she studied the biomechanics and muscle physiology of fishes. She received her Master's in Biology with a concentration in Physiological Ecology from Sonoma State University, where she focused on the role of adipose-derived hormones in Northern elephant seals. Caroline is a student in Michelle Shero's lab where she will be studying the reproductive physiology of Weddell seals. In her free time, she enjoys backpacking, running, and gardening. |

Isabel Honda graduated from the University of California, Berkeley in Applied Mathematics with a concentration in Environmental Engineering and a minor in the Energy and Resources Group. Her undergraduate research at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab focused on enhancing fungal enzyme secretion for biofuel production and mathematical techniques to model these processes. She is now a member of the Ji lab, where she is interested in modeling the impacts of climate change on coupled biological-physical interactions and plankton population dynamics. In her free time, Isabel enjoys analyzing classic novels, hiking, and playing the saxophone (fun fact: she performed in the Super Bowl 50 Halftime Show with the Cal Marching Band!). |  Zoe Aarons graduated from Bowdoin College with a B.A. in Earth and Oceanographic Science and a minor in Computer Science. As an undergraduate, she studied chemical proxies in bamboo corals as well as tropical cyclones in climate models. After spending a year as a research assistant at the University of Washington, she is excited to join the Follows lab where she will use numerical models to study phytoplankton ecology and investigate the impacts of climate change on phytoplankton diversity and productivity. Outside of work, she enjoys cooking, hiking, and spending time outdoors. |

Nadège Aoki graduated from Cornell University with a B.A. in Biological Sciences, concentrating in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. As an undergraduate she studied the biomechanics of marine polychaetes at the Smithsonian and wrote an honors thesis on the taxonomic diversity of West African weakly electric mormyrids. After undergrad she spent time working at the National Science Foundation. Nadège has joined Aran Mooney's lab to study the physiological and behavioral effects of the ambient soundscape on coral reef fishes and invertebrates. In her spare time she enjoys reading, cooking, and watching movies with her tuxedo rescue cat, Algernon. |  Evie Fachon is working with Donald Anderson studying harmful algal bloom dynamics in the Alaskan Arctic. She graduated Northeastern University in 2017 and has spent the past three years working as a research assistant at WHOI and at the University of Otago (Dunedin, New Zealand). When she is not cruising in the Arctic she can be found hiking with her dog or exploring the rocky New England coastline. |